Australia post-COVID: Population and retail sales outlook

This post was originally published on SCN Australia.

On 28 June 2021, the Australian Department of Treasury released the fifth Intergenerational Report (IGR) – the first since the COVID-19 crisis. The IGR, issued every five or six years, projects the outlook for the Australian economy and the federal government’s budget over the next four decades. The COVID-19 pandemic, which has caused the most severe global economic shock since the Great Depression – although nowhere near as long-lasting – has profoundly affected the outlook.

One of the most significant changes seen in Australia as a direct result of COVID-19 is the fall in population growth, resulting from the absence of net overseas migration (NOM) since early 2020.

The IGR identifies Australia’s greatest demographic challenge as the ageing population, caused by increasing life expectancies and falling fertility rates

The IGR identifies Australia’s greatest demographic challenge as the ageing population, caused by increasing life expectancies and falling fertility rates. The ratio of working-age people to those over 65 (known as the old-age dependency ratio) was 6.6 in 1981/82 (ie. for every person aged over 65, there were 6.6 working age people) but has reduced over time to 4.0 at 2019/20. The IGR projects that this ratio will fall to just 2.7 by 2060/61 under the assumptions that net migration continues at more or less the levels achieved over the past decade or so, (ie. a net 235,000 new migrants to Australia each year, after recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. Clearly, such a dramatic reduction in the old-age dependency ratio will pose serious fiscal and social challenges for Australia.

The basis of this quite startling projection in the IGR is the expectation that net migration to Australia will be negative in 2020/21 (-97,000) and 2021/22 (-77,000). Net overseas migration is forecast to steadily recover to 235,000 people per year by 2024/25 and is then assumed to stay at that level until the end of the projection period.

The fall in migration is not the sole factor in the projected reduction in future population growth since the fertility rate, which obviously drives natural increase, is also forecast to decline. Deaths are projected to continue to increase faster than births, due to the ageing population, and the contribution of natural increase to population growth is forecast to fall to about one-quarter of annual population growth by 2060/61, compared with 44% of population growth during the past 20 years. But net migration will remain the key lever that will determine national population growth outcomes.

The long run assumption of 235,000 per year in net migration is based on current government policy, allowing for planning levels in the permanent migration program (190,000 people per annum), the humanitarian program (13,750 people per annum), and assumed flows of temporary migrants, Australian citizens and departing permanent residents in line with historical averages.

So, is it now a given that population growth in Australia over the next four decades will be significantly lower than might have been expected pre-COVID?

The short answer is no – it is certainly possible, but not a given since the Australian government can choose to alter the migration program at any point and, historically, such alterations have been commonplace. The assumed levels of annual net migration underpinning IGR reports, for example, have varied from just 90,000 in the 2002 report to 235,000 in the 2021 report, and have increased steadily with each progressive report.

Our current population of 25.7 million is almost three million greater than was projected at this point in the IGR published in 2002 and, the 2021 report points out, has been reached 20 years earlier than was projected in the 2002 IGR. So, we can reasonably conclude that Intergenerational reports do not have a great track record on population forecasting, although, to be fair, the level of net migration, especially prior to 2006, has varied enormously.

The 2021 IGR points out that a well targeted, skills focused migration program can increase the stock of working-age people and slow the transition to an older population, thereby improving Australia’s fiscal outcomes

The 2021 IGR points out that a well targeted, skills focused migration program can increase the stock of working-age people and slow the transition to an older population, thereby improving Australia’s fiscal outcomes. The report also presents a sensitivity analysis that allows for an increased level of net migration over the projection period so that the annual net migration level remains a constant 0.8% of the Australian population, resulting in up to 327,000 net migration per year by 2060/61, compared with 235,000 people per year in the baseline projections. That change alone would generate an increase in population of 1.7 million people over the period, or 4.3%, compared with the baseline projections, made up of an additional net 1.3 million migrants and 0.3 million extra births attributed to those additional migrants.

So, I suggest that we do not jump too quickly to conclusions about reductions in Australia’s long-term population growth attributable directly to COVID-19. The reality is that our long-term population projections have always been fluid and they remain so. Importantly, the Australian government has at its disposal an important and effective lever – annual net migration – that it can pull in order to effect changes in long-term outcomes.

What is indisputable, though, is that there already has been, and over the next few years at least, will continue to be, a significant short-term reduction in population growth. That begs the question what will the impacts be of this short-term reduction?

The most recent data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (at December 2020) shows that Australia’s population increased by 130,000 (0.5%) over the year, to 25.7 million. This was one-third of the annual growth achieved pre-COVID but it was nonetheless some growth, reflecting the fact that the first three months of the year were pre-COVID lockdown and a significant number of expats returned to Australia during the year, offsetting the level of net migration from the country. However, over the next two years, it is expected that there will be little or no growth in Australia’s population and perhaps even some slight decline.

To this point, the observed outcomes throughout the various cities and regions of Australia have been partly in line with expectations but also, in some ways, surprising. The CBDs of our major cities have clearly suffered severely from the reduction in net migration, accentuated by the plight of universities. Overseas students, primarily from Asia, made enormous contributions to the vitality of our central business districts, particularly in Sydney and Melbourne, and their absence in the post-COVID period is very apparent. There is little surprise, therefore, that our CBDs and inner-city areas have seen some depopulation generally.

Growth corridors strengthen

What is surprising though is the fact that the outer suburban growth corridors of the capital cities – in particular Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane – have continued to grow strongly in the post-COVID period up to this point. Many new residential estates have struggled to keep up with demand in areas such as the Cranbourne and Craigieburn growth corridors of Melbourne, the south-western growth corridor of Sydney, and the Ipswich growth corridor of Brisbane. Given that net migration to Australia pre-COVID was driven primarily by Asian arrivals, including India, and given that many of those new migrants settled in the outer suburban growth areas of our state capital cities, it seems counter-intuitive that demand for new housing in those growth areas has remained so strong during 2020 and into 2021.

The answer lies in a combination of factors, including initiatives by governments to stimulate home purchases (first home owner grants), the fact that new migrants typically take a few years before being in a position to purchase their first home (meaning that the reduction in net migration will take a number of years before it translates into a reduction in demand for new dwellings) and perhaps also the short-term lifestyle changes induced by the COVID-19 pandemic, (ie. the search for more space).

Such changes were also manifest in an observed increase in net internal migration away from the capital city to regional areas in both NSW and Victoria during 2020, reversing the long-term pattern of net internal migration to Australia’s largest cities. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, Melbourne saw a drift of 26,000 to other areas in 2020 while, for Sydney, the loss to other areas was even greater, at 31,500. Again, though, let’s not jump to too many conclusions too early on this trend. As the situation returns back closer to ‘normal’, I fully expect the allure of the state capitals to return.

So, realistically, the population impacts on outer suburban growth areas resulting from lower, or zero, levels of net migration are unlikely to flow through for another year or so. It seems unlikely that such impacts can be avoided forever and will not eventually flow through to at least a short-term fall in population growth for outer suburban growth corridors, most likely by around 2023/24 and lasting a few years. However, the extent of any such reductions will depend on the degree to which inner-city residents might replace migrants as new home purchasers over this period.

For our inner-city areas, the most important short-term initiative that can replace the recently lost population is the return of international students for our tertiary education institutions, with returns hopefully commencing during 2022

For our inner-city areas, the most important short-term initiative that can replace the recently lost population is the return of international students for our tertiary education institutions, with returns hopefully commencing during 2022.

Over the longer-term, it is not only possible but almost to be expected that the national net migration program could be adjusted, even if just for a few years, to replace at least some of the loss in population that is expected for Australia in 2021 and 2022.

Impact on retail?

What has this recent reduction in population growth meant for the Australian retail sector?

The ABS retail turnover data published monthly in its Retail Trade Series paints a very interesting picture, one that in many regards is different to what might have been expected so far.

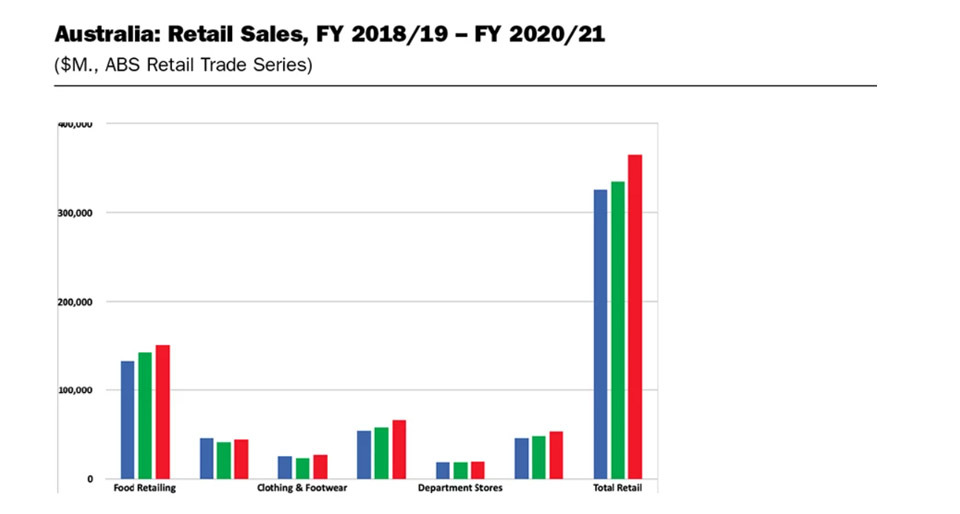

Looked at in isolation, without the benefit of knowing that Australia has been ravaged by a global pandemic over the past 18 months, one could be forgiven for thinking that the retail sector, broadly, has enjoyed nothing but good times. As the chart below shows, retail sales nationally have grown significantly in both FY2019/20 (+3.2%) and especially FY2020/21 (+8.9%).

Furthermore, all retail categories other than hospitality (cafés, restaurants and take-away food) have enjoyed very strong trading conditions during the past two years. Even the much-maligned department stores category has seen a dramatic reversal in its trading fortunes during the COVID period, with sales remaining flat in FY2019/20 but then jumping by 6.3% in FY2020/21.

Food retailing and household goods retailing have particularly made hay during the past two years, despite – or because of – the COVID pandemic.

Most retail categories have traded at far better levels since the pandemic arrived than they were travelling pre-pandemic, as consumer spending has shifted heavily to retail in lieu of other discretionary avenues, such as travel and holidays, especially internationally.

Most retail categories have traded at far better levels since the pandemic arrived than they were travelling pre-pandemic, as consumer spending has shifted heavily to retail in lieu of other discretionary avenues, such as travel and holidays, especially internationally

Even the hardest hit sector, hospitality, has largely bounced back as soon as lockdowns have been eased. Total turnover for cafés, restaurants and take-away food stores fell 8.6% in 2019/20 but increased by 5.7% in 2020/21, despite numerous lockdowns across various parts of the country during the year and despite the continuing absence of workers from CBDs. The sector in total is still slightly down on pre-COVID levels, however, many operators have found new ways of doing business with very effective Click & Collect and delivery campaigns.

The hospitality sector is suffering again with the recent lockdowns in NSW and Victoria but has demonstrated that it will bounce back quickly once the lockdowns are able to be eased, hopefully sooner rather than later.

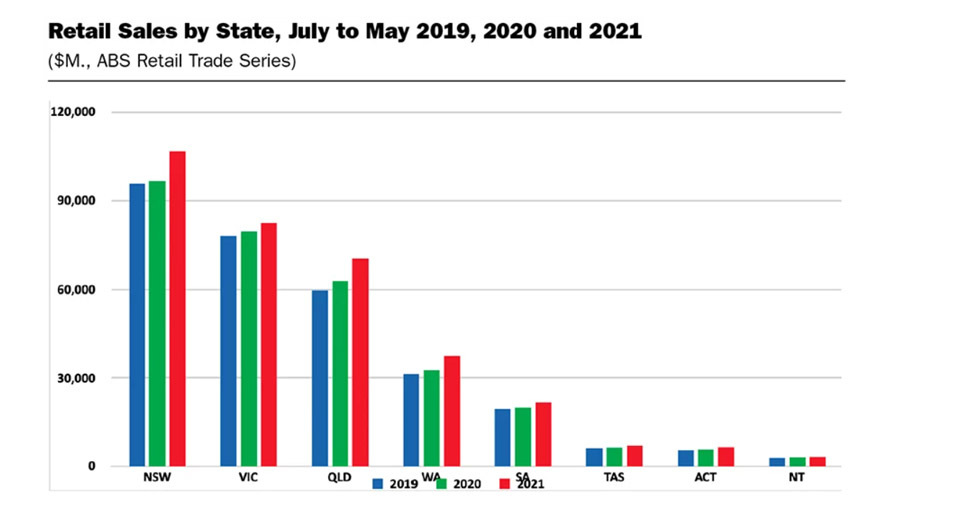

The chart below shows that all states – including Victoria, which has undergone the longest period of lockdown – have recorded substantial increases in total retail turnover during the past two years. The increases have been particularly marked in New South Wales, Queensland and Western Australia, especially in FY2020/21, although the current lockdown in NSW is likely to curb this growth pattern, at least for the short term.

And finally, a word of encouragement. Don’t feel too guilty when reaching for that comforting G&T or bottle of wine to help deal with lockdowns, working from home, home schooling, and everything else that has come with the pandemic, including the sheer sense of frustration. You are not alone in doing so. Packaged liquor retailers enjoyed sales growth of 12.3% in FY2019/20 and a massive 15% in FY2020/21 – partly in celebration as the light appears at the end of the tunnel with vaccination but, more likely, in continuing self-consolation for the seemingly never-ending lockdowns.

Now, if only as a nation we can tackle the challenges of vaccination with similar enthusiasm!